Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian

| Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian 閩南護法區 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de facto autonomous region of the Republic of China | |||||||||

| 1918–1920 | |||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||

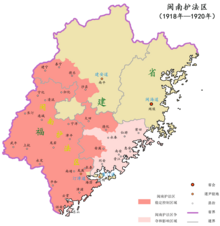

Map of the Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian Areas stably controlled by the Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian

Areas contested and influenced by the Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian

The rest of Fujian Province | |||||||||

| Capital | Longxi (Zhangzhou) | ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional Protection Junta | ||||||||

| • Type | Anarchist civil-military government | ||||||||

| • Motto | "Fraternity, Liberty, Equality, Mutual aid" “博愛、自由、平等、互助” | ||||||||

| Commander-in-chief | |||||||||

• 1918–1920 | Chen Jiongming | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1 September 1918 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 12 August 1920 | ||||||||

| Subdivisions | |||||||||

| • Type | County | ||||||||

| • Units | 26 counties | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | China ∟Fujian | ||||||||

The Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian (Chinese: 閩南護法區; pinyin: Mǐnnán hùfǎ qū)[1][a][b] was a de facto autonomous region of Republic of China established by the "Guangdong Army to assist Fujian" (Chinese: 援閩粵軍; pinyin: Yuánmǐn yuèjūn)[c] led by General Chen Jiongming. The regional administration controlled 26 counties of southern and western Fujian, with Zhangzhou as its capital, where it implemented some policies with anarchist characteristics.

The regional administration was established during the Constitutional Protection Movement, when Chen's forces fought to defeat the Northern warlords of the Anhui and Zhili cliques, and reassert constitutionalism in southern China. After moving into Fujian and fighting against the northern forces of Li Houji, Chen's Guangdong Army established control over the southern part of the region. Zhangzhou subsequently became a centre of the New Culture Movement, which established newspapers to propagate its ideas of "liberty", equality", "fraternity" and "mutual aid". Anarchists and communists were also attracted to the region, where under Chen's protection, they were able to agitate and organize with full freedom of speech and freedom of association.

In the capital of Zhangzhou, the city's defensive walls were demolished in order to make way for carriageways and public parks. The administration also established a comprehensive education system, sending several students to France as part of the work-study program. The reforms carried out were extensive and received popular support, as they improved societal infrastructure and welfare, while also keeping taxes relatively low. The reforms attracted the attention of the Russian Soviet Republic, which dispatched a representative to establish relations with the regional administration. This also drew the attention of American and British intelligence, which were worried by the rise of "Bolshevism" in the region.

With the outbreak of the Guangdong–Guangxi War, the majority of Chen's Guangdong Army left the region in order to fight against the Guangxi clique and retake control of Guangdong. For a few months, a small garrison was left behind in Southern Fujian, which was eventually handed back over to the forces of Li Houji.

History[edit]

Capture of Southern Fujian[edit]

By 1917, northern warlords had seized control of the Beiyang government. Revolutionaries in southern China responded by launching the Constitutional Protection Movement, calling for the restoration of the constitutional order.[7] In October 1917, Chen Jiongming was appointed as commander-in-chief of the Guangdong Army, which was already planning a military expedition against the government.[8]

The warlords of the Anhui and Zhili cliques sent their forces south to pacify the rebellion in Guangdong, acting with the assistance of Fujian's military governor Li Houji. Chen responded by ordering the Guangdong Army to "assist Fujian" (Chinese: 援閩粵軍; pinyin: Yuánmǐn yuèjūn) and bring it under the rule of the Constitutional Protection Junta. They transferred to Shantou, where Chen began recruiting thousands of people into his army.[9] He established an arsenal in Shanwei, laid out an extensive military logistics network by building new roads and supply stations, and organised local militia to counter banditry and carry out guerrilla warfare against invading forces. He did this with little help from Guangdong's military governor Mo Rongxin, who denied him necessary funding, hoping to limit his growing influence.[10]

Li went ahead with his plans to attack Guangdong, recruiting thousands of people from Northern Fujian into his own army.[11] On May 1918, Li attacked Guangdong, but faced heavy resistance from Chen's Guangdong Army and guerrilla militias. In August, Chen's forces mounted a counteroffensive and quickly advanced into Fujian. By the end of the month,[12] they had captured the province's southern capital of Zhangzhou, which Chen established as his base of operations,[13] while Li's army held onto its territory in Xiamen. In November 1918, the two sides arranged a brief armistice.[12] Although Li received reinforcements from the north, the looting and arbitrary attacks carried out by the northern soldiers against the local population alienated the people of Fujian, who began cooperating with the Guangdong Army. By the end of 1918, Chen's numerically inferior forces had captured more than half of Fujian province.[14]

New Culture Movement[edit]

With a new base area in Minnan, Chen Jiongming began putting his ideas for reform into practice, building strong civilian institutions while maintaining his military strength.[15] By this time, members of the New Culture Movement had begun calling for far-reaching modernizing reforms, including democratization, humanitarianism, scientific progress and mutual assistance.[16] Chen's former teacher Zhu Zhixin invited members of the New Culture Movement to Zhangzhou, in order to carry out reforms, educate the populous and transform southern Fujian into a sustainable autonomous region. Chen himself believed that such a region could serve as a model for reforming the entire country, based on his federalist ideology.[17]

Some of the new invitees established a semi-weekly magazine, Minxing[18] (Chinese: 閩星; English: Fujian Star), which was dedicated to discussion of reformist ideas; they also established a daily newspaper, Minxing rikan[18] (Chinese: 閩星日刊; English: Fujian Star Daily News), which reported on global and local affairs and criticised existing traditions.[19] Chen Jiongming himself frequently wrote for the magazine, penning critiques of the reform programs of Kang Youwei and Dai Jitao, publishing letters to and from the Chinese Women's Association, and even contributing poems to the publication. Aiming to reach the greatest number of readers, the magazine's editor Chen Qiulin (陳秋霖) made sure that all its works were published in written vernacular Chinese.[20] The magazine published articles on many different subjects, including articles on sexuality, morality and religion; articles about the Russian Revolution, such as critiques of the Soviet Russian Constitution; and historical reports on Korean and Taiwanese independence struggles against the Empire of Japan.[21] It also included contributions from Zhu Zhixin, Wang Jingwei and Hu Hanmin, who respectively wrote about societal, commercial and environmental reforms.[22] Anarchists such as Liang Bingxian (梁冰弦) also contributed to the publication.[23]

Chen Jiongming wrote extensively in Minxing about his views on the New Culture movement's philosophy. He believed that China ought to follow a process of sociocultural evolution, based in mutual aid, which he believed would eventually transform the country into a stateless society of social equality. In order to achieve this, he advocated for widespread "thought reform", while cautioning against the use of indoctrination or brainwashing.[24] Chen also argued against individualism and nationalism, the latter of which he considered to be a way for "ambitious politicians" to "fool their people and bully the world", culminating in militarism and imperialism.[25] Influenced by a synthesis of Social Darwinism and anarchism, Chen concluded his anti-nationalist remarks by calling for a "socialism of all mankind", based in fraternity and mutual aid.[26] He believed that China could "work for the benefit of the world", but it had to start with internal reform, specifically thought reform.[27] Chen also wrote the manifesto of Minxing rikan, in which he outlined its aims of liberty, equality and mutual aid.[28]

Anarchist and communist activity[edit]

As early as 1918, anarchist followers of Liu Shifu had moved from Guangdong to Fujian, in order to join up with Chen Jiongming.[29] Chen, who was a former comrade of Shifu and sympathetic to anarchism, gave the anarchists his protection to operate with full freedom of association and freedom of the press.[30] By early 1920, Fujian had become a center of the anarchist movement in China.[23] During the May Fourth Movement, anarchist societies were organised in Zhangzhou and other cities, where they published periodicals and organised mass mobilisations.[31]

Although some anarchists had turned against Bolshevism by the outbreak of the Red Terror in early 1919, even a year later, other anarchists still supported it, considering it closely comparable to anarchism. Led by Liang Bingxian, the Fujian anarchist movement became a major source for news about the Russian Revolution. The Fujian anarchists were even contacted in March 1920 by the Communist International's official Grigori Voitinsky, who had been sent to China to organise the local communist movement. When Chen Duxiu started transforming New Youth into a nucleus for the foundation of the Chinese Communist Party, he appointed the Fujian anarchist Yuan Zhenying as its editor. With all this anarchist and communist activity,[32] Chen's government became known in some circles as the "Soviet Russia of Southern Fujian".[33]

In April 1920, the United States Department of State requested a report on the rise of "Bolshevism" in the region from the US consulate in Amoy.[34] The report indicated that Bolshevism was gaining influence in Zhangzhou, where schools were teaching socialist doctrine and anarchist communist pamphlets were being circulated, some even by Chen Jiongming himself, who was also reported to have described Jesus as a socialist.[35] At this time, the United States officials considered "Bolshevism" to be synonymous with "anarchism".[36]

Relations with Soviet Russia[edit]

In early 1920, the regional education bureau was contacted by a Russian communist, who told them that the government of the Russian Soviet Republic had become interested in the revolutionary movement in southern Fujian and hoped to establish mutually-beneficial relations between the two.[37] Chen agreed to meet with the Soviet representative, after consulting Zhu Zhixin and Liao Zhongkai.[38] On April 29, 1920, Chen, Zhu and Liao met secretly with the Soviet representative, General Alexey Potapov. Chen was given a letter from Vladimir Lenin, who suggested that Chen engage more with mass politics, particularly the peasant movement, and offered to provide arms to the Guangdong Army.[38] As Zhangzhou lacked a harbor, Chen declined the offer.[39] In his letter to Lenin, Chen expressed support for Lenin and his cause, hoping that "the new China and the new Russia will join hands like intimate friends" and declaring, "I firmly believe that Bolshevism will benefit humanity, and I am willing to do my best to spread the principles of Bolshevism to the world."[18]

Potapov subsequently met with Chen Qiyou and members of the Minxing editorial staff, including Liang Bingxian. Liang informed Potapov that, as "freedom socialists", they upheld the rights to freedom of expression and freedom of thought, and were critical of the Russian Soviet Republic for its violations of human rights.[40] When Potapov asked whether they thought that counterrevolutionary tendencies ought to be politically repressed, Liang responded: "we believe in carrying out social revolution to achieve social justice. Once social justice is achieved, the people will support it wholeheartedly; no madman will ever be able to destroy it... But if we used destructive force to interfere with freedom, we ourselves would become the counter-revolutionaries."[40] Despite the secrecy of the meetings, American and British intelligence quickly picked up reports about it and began referring to Chen as a "Bolshevik general". The US consul at Amoy reported an increase in Bolshevik propaganda and described Chen as a socialist, although not a particularly radical one.[41]

Withdrawal[edit]

When fighting broke out between the Northern Anhui and Zhili cliques in 1920, Chen decided to move against the Northern warlords.[42] Chen never intended to stay for long in southern Fujian; his aim was to eventually return to Guangdong and oust the Guangxi clique, who themselves knew this was his plan. Guangxi troops were dispatched to Fujian, under the pretext of attacking Li Houji's forces, and the clique requested that Chen take his Guangdong Army north to fight in the vanguard against Li.[43] He agreed, on the condition that the Guangxi clique supplied his army with ammunition and payment, and that they not move into the province while his army was on the frontlines; he also counter-offered that the Guangxi army themselves go to fight in northern Fujian, while the Guangdong Army remained behind in the south.[44]

By mid-1920, the Guangxi army had begun openly moving against Chen's forces. On August 12, 1920, Chen ordered the Guangdong Army to go on a counteroffensive, to return south and retake Guangdong. He led 80 battalions south, where they fought in the Guangdong–Guangxi War. 22 battalions stayed behind in southern Fujian, but by January 1921, they had formed an agreement with Li Houji to relinquish the south to his rule, so that they could themselves return to Guangdong.[44] In total, the Constitution Protection Region lasted for two years and four months.[45]

Administration[edit]

Government[edit]

The Constitutional Protection Region of Southern Fujian was administered by a combined civil-military government, which oversaw the region's economic and military consolidation. As commander-in-chief of the Guangdong Army, the region's de facto supreme ruler was Chen Jiongming, who appointed the administration's departmental heads.[1]

| Office | Officeholder |

|---|---|

| Commander-in-chief | Chen Jiongming |

| Chief of staff | Deng Keng |

| Head of civil affairs | Xu Fu |

| Head of finance | Zhong Xiunan (鍾秀南) |

| Head of education | Liang Bingxian (梁冰弦) |

| Head of public works | Zhou Xingnan (周醒南) |

| Police commissioner | Qiu Zhe |

| Head of public health |

Chen believed that the country needed full public participation in government, rather than a "totalitarian government", whether autocratic or oligarchic.[46] Liang thus proposed that Chen discard the title of commander-in-chief, believing he could do "more good for the society as a simple ordinary citizen". But although Chen sympathised with anarchist arguments against taking power, he believed that, if he was not the one in power, it could have been taken by someone worse.[47]

Administrative divisions[edit]

The Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian consisted of 26 counties, in South Fujian and West Fujian, including:[18]

|

|

Additionally, the Guangdong Army also contested for control over counties such as Putian, Xianyou, Yongchun, Nan'an, Jinjiang, Tong'an and Hui'an in Fujian with other local armed forces.[18]

Economy and social policy[edit]

Public works[edit]

With Zhou Xingnan appointed to head public works, the regional administration undertook a program to reform municipal infrastructure, aiming to turn Zhangzhou into China's first modern city. Over the course of six months, the administration demolished the city's defensive walls to make way for new infrastructure, building the city's first carriageways and public parks.[1] In one of the parks, they erected a monument inscribed with the words "liberty" (Chinese: 自由; pinyin: zìyóu), "equality" (Chinese: 平等; pinyin: pingděng), "fraternity" (Chinese: 博愛; pinyin: bó'ài) and mutual aid (Chinese: 互助; pinyin: hùzhù), the four principles of the New Culture Movement.[22] Zhangzhou also saw the construction of its first reinforced concrete bridge, first urban-rural road network, and first bank. Additionally, a factory for the poor, a grand hotel for guests, and a special district for prostitutes were established, and advanced agricultural production equipment was introduced.[48]

According to the American consul in Amoy, these public works were funded by progressive taxation, which was lower even than the Northern government's own taxes, and were largely welcomed by the general population. He contrasted Zhangzhou with the northern-occupied Amoy, "the dirtiest city in China", which had seen no meaningful improvements to public welfare in spite of the heavier taxation.[49] According to Liang Bingxian, the infrastructure projects made Chen "a hero to those who were concerned with the material improvement and reconstruction of China."[50]

Education[edit]

At Liang Bingxian's suggestion, and with the support of Zhu Zhixin, the civil-military administration established an education bureau.[51] Liang himself was appointed to head the region's education program.[52] In order to aid in the region's education and publication efforts, in late 1919, Liang brought several educators, mechanics, printers and writers to the region.[53] The education bureau held an education conference, attended by school administrators and teachers from all of the region's 26 counties. Lectures were given by Wu Zhihui, who discussed the simplification of Chinese characters and the adoption of a phonetic alphabet, and Li Shizeng, who talked about democratic revolution.[51]

While maintaining support for primary education, the administration aimed to make higher education more accessible to the province's students. At least two students from every county in the region were sent to France, where they participated in work-study programs. Chen himself paid for more than 80 students to study abroad, including some future leaders of the Chinese Communist Party,[54] such as the future Trotskyist leader Zheng Chaolin.[55] The French study program was enthusiastically supported by Nationalist intellectual Wang Jingwei, who, in a speech to a teachers' college in Zhangzhou, proposed the creation of a university in southern China. Chen himself requested funds from the council in Guangdong for such a project, looking at possible construction sites and calling for officials to be appointed to oversee the project.[53]

Chen Jiongming actively recruited talents nationwide, including a group of "liberal socialists" (followers of Chinese anarchist Liu Shifu), to assist him in educational efforts and the establishment of the university. The administration also set up study centers and education commissioners in each county, reforming old textbooks. They established modern schools in rural areas, aiming for "one school per village," banning private schools and setting up normal schools, general high schools, vocational schools, night schools for commoners, and women's home economics training institutes. In 1920, they also established women's normal training institutes and women's vocational schools, setting up more than 90 night schools in the same year.[55]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Also translated as the "Southern Fujian Area for Constitutional Protection".[2]

- ^ Initially known as the "Constitution Protection Region of Fujian" (Chinese: 福建護法區; pinyin: Fújiàn hùfǎ qū).[3]

- ^ Also translated as the "Aid-Fujian Cantonese Army".[4] Commonly shortened to "Guangdong Army",[5] or "Cantonese Army"[6]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Chen 1999, p. 86.

- ^ Goikhman 2013, pp. 81–82.

- ^ 闽南日报 (2019-02-27). "漳州现99年前民国粤军地契 见证一段历史" (in Simplified Chinese). 台海网. Archived from the original on 2023-04-22. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

1918年6月,陈炯明与李厚基达成划界停战协议,在粤军所占区域建立"福建护法区"(后称"闽南护法区"),首府设于漳州。

[In June 1918, Chen Jiongming and Li Houji reached a boundary ceasefire agreement, establishing the "Constitution Protection Region of Fujian" (later known as the "Constitution Protection Region of Southern Fujian") in the area occupied by the Guangdong Army, with its capital in Zhangzhou.] - ^ Guo 2020, p. 7.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 75–77; Goikhman 2013, p. 85.

- ^ Guo 2020, p. 7n24.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 74.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 75.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 77.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b Chen 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 76; Guo 2020, p. 7.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 78.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 79.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e 张慧卿 (2005). 闽南护法区研究 (Master thesis) (in Simplified Chinese). 福建师范大学. Archived from the original on 2022-02-12. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 81.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Chen 1999, p. 82.

- ^ a b Dirlik 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 83.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 84.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 85.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Dirlik 1991, pp. 151, 170.

- ^ Dirlik 1991, p. 170.

- ^ Dirlik 1991, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Dirlik 1991, p. 179.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 88; Dirlik 1991, p. 179.

- ^ Dirlik 1991, p. 150.

- ^ Dirlik 1991, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Dirlik 1991, p. 151.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b Chen 1999, p. 92.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b Chen 1999, p. 93.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Chen 1999, p. 98.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 95.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 90.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 90–91.

- ^ 陈福霖(F. Gilbert Chan) (1989-11-01). 南粤割据:从龙济光到陈济棠 (in Simplified Chinese). 广州: 广东人民出版社. p. 382. ISBN 9787218002828. Archived from the original on 2023-07-26. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

城墙拆除改成道路,成立妓女户特区,道路拓宽、新屋不少

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 87.

- ^ Chen 1999, p. 86; Goikhman 2013, p. 82.

- ^ a b Chen 1999, p. 88.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 86, 88.

- ^ a b Chen 1999, p. 89.

- ^ Chen 1999, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b 张慧卿 (2008). "陈炯明与闽南护法区的政治革新". 宁德师专学报(哲学社会科学版) (87): 96–100.

Bibliography[edit]

- Chen, Leslie H. (1999). Chen Jiongming and the Federalist Movement: Regional Leadership and Nation Building in Early Republican China. University of Michigan. ISBN 0-89264-135-5. LCCN 98-55065.

- Dirlik, Arif (1991). Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520072978. OCLC 1159798786.

- Goikhman, Izabella (2013). "Chen Jiongming: Becoming a Warlord in Republican China". In Leutner, Mechthild; Goikhman, Izabella (eds.). State, Society and Governance in Republican China. LIT Verlag. pp. 77–101. ISBN 978-3-643-90471-3.

- Guo, Vivienne Xiangwei (2020). "Not Just a Man of Guns: Chen Jiongming, Warlord, and the May Fourth Intellectual (1919–1922)". Journal of Chinese History. 4 (1): 161–185. doi:10.1017/jch.2019.22. hdl:10871/39039. ISSN 2059-1632.

Further reading[edit]

- 汤锐祥 (1992). 护法舰队史 (in Simplified Chinese). 广州: 中山大学出版社. p. 278. ISBN 9787306005113. Archived from the original on 2023-08-18. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

另一方面,11月30日,军政府政务会议发布任命令,特任护法舰队总司令林怿为福建督军,陈炯明为福建省长;12月12日,又发布补充令,任命福建省长陈炯明兼会办福建军务,方声涛会办福建军务。

- 闽台文化大辞典 (2019-04-25). "闽南护法区的建立" (in Simplified Chinese). 福建炎黄纵横. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- Chen Jiongming Anarchism and the Federalist State