Albertina Sisulu

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

Albertina Sisulu | |

|---|---|

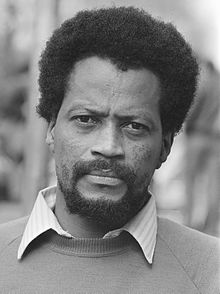

Sisulu in April 2007 | |

| Born | Nontsikelelo Thethiwe 21 October 1918 |

| Died | 2 June 2011 (aged 92) |

| Known for | Anti-apartheid activism |

| Political party | African National Congress |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

Albertina Sisulu OMSG (née Nontsikelelo Thethiwe; 21 October 1918 – 2 June 2011)[1] was a South African anti-apartheid activist. The wife of fellow activist Walter Sisulu, she was affectionately known as "Ma Sisulu" throughout her lifetime by the South African public.

Early life and education[edit]

Sisulu was born on 21 October 1918 in the Camama, a village in the Tsomo region of the Transkei.[2] She was the second of five siblings in a Xhosa family. Her father, Bonilizwe Thetiwe, was a migrant worker who spent long stints working in the gold mines of the Transvaal, and her mother, Monica Thetiwe (née Mnyila), was disabled by the bout of Spanish flu that she had suffered while pregnant with Sisulu.[2][3] Sisulu and her siblings spent most of their childhood with their maternal grandparents in the village of Xolobe, where Sisulu began school at a Presbyterian mission. Though her family called her "Ntsiki" throughout her life, she assumed the name Albertina at school, choosing it from a list of European Christian names provided by her missionary schoolteachers.[2]

In 1929, while Sisulu's mother was pregnant with her fifth and final child, Sisulu's father died of occupational lung disease in Camama.[2] Her mother remained in ill health until her death in 1941, so Sisulu – both the eldest sister and the eldest female cousin – became a primary caregiver to her younger siblings and cousins, with frequent interruptions to her education as a result.[2][4] Nonetheless, in 1936, she received a scholarship for secondary schooling at Mariazell College, a Catholic boarding school in Matatiele.[2] She covered her living expenses by ploughing fields and working in the laundry room during school holidays.[3] Newly converted to Catholicism, she intended to become a nun or school principal, but her headmaster, Father Bernard Huss, convinced her to pursue training as a nurse after she finished school in 1939.[3]

Anti-apartheid activism[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

In January 1940, Sisulu moved to Johannesburg, where she began her long nursing career as a trainee in the non-European section of the Johannesburg General Hospital.[3] Her interest in politics grew through her association with Walter Sisulu, an activist of the African National Congress (ANC), who courted and then married her.

1948–1964: Pre-Rivonia Trial[edit]

Sisulu did not display an interest in politics at first, only attending political meetings with Walter in a supporting capacity, but she eventually got involved in politics when she joined the ANC Women's League in 1948, and took part in the launch of the Freedom Charter the same year. Sisulu was the only woman present at the birth of the ANC Youth League.[5] She became a member of the executive of the Federation of South African Women in 1954.

On 9 August 1956, she joined Helen Joseph and Sophia Williams-De Bruyn in a march of 20,000 women to the Union Buildings of Pretoria in protest against the apartheid government's requirement that women carry passbooks as part of the pass laws.[5] "We said, 'nothing doing'. We are not going to carry passes and never will do so." [citation needed] The day is celebrated in South Africa as National Women's Day. She spent three weeks in jail before being acquitted on the pass charges, with Nelson Mandela as her lawyer. Sisulu opposed Bantu education, running schools from home.[citation needed]

Sisulu was arrested[when?] after her husband skipped jail to go underground in 1963, becoming the first woman to be arrested under the General Laws Amendment Act of 1963 enacted in May. The act gave the police the power to hold suspects in detention for 90 days without charging them. Sisulu was placed in solitary confinement for almost two months until 6 August.[2]

She recruited nurses to go to Tanzania, to replace British nurses who left after Tanzanian independence. The South African nurses had to be "smuggled" out of SA into Botswana and from there they flew to Tanzania.[citation needed]

1964–1989: Post-Rivonia Trial[edit]

In mid-1964, in the aftermath of the Rivonia convictions, Sisulu was served with the first in a series of banning orders; she was banned continuously for the next 17 years, prohibited from political activity and for several years confined to effective house arrest.[2] The Minister of Law and Order allowed her fourth ban to lapse in August 1981, and she celebrated by making an address – her first political speech since the early 1960s – at a local church's commemoration of the Women's March.[6] The respite lasted less than a year before she was arrested and served with another banning order, her fifth, in June 1982;[2][7] that order was part of a more general crackdown effected in Soweto during commemorations of the 1976 Soweto uprising.[8]

Sisulu's June 1982 banning order was allowed to lapse a year later,[9] but she was arrested soon afterwards and served with criminal charges for participating in the activities of the banned ANC.[10]

She was subsequently in and out of jail for her political activities, but she continued to resist against apartheid, despite being banned for most of the 1960s. She was also a co-president of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in the 1980s.[11]

From 1984 until his murder in 1989, she worked for Soweto doctor, Abu Baker Asvat, who allowed her to continue with her political activities while employed by him, and she was present when he was murdered. Sisulu regarded her relationship as being that of a "mother and a son", and the two never allowed the rivalry between the UDF, and Azapo, of which Asvat was the Health Secretary, and a founding member, to interfere with their friendship or working relationship.[12]

She was banned again in early 1988.[13][14]

1989–1994: Negotiations[edit]

In 1989, as the negotiations to end apartheid quickened, Sisulu embraced her public-facing role in the anti-apartheid movement. In June that year – only days after her latest banning order was renewed – Sisulu was granted her first South African passport.[15] Later that month, she led a UDF delegation on an international tour, which included a meeting with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.[16] While in London, she addressed a major rally of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement.[17] At the conclusion of the tour, on 30 June 1989, she met with American President George H. W. Bush in the White House.[18][19] After her husband was released from prison, the Sisulus returned to the United States for a broader tour in October 1991.[20]

Meanwhile, President F. W. de Klerk's government unbanned the ANC in 1990, permitting the party to resume overt organising inside South Africa. Sisulu became involved in the campaign to re-establish the ANC Women's League, though she declined a nomination to stand for the league's presidency. Instead, at the league's first national conference in Kimberley in April 1991, she threw her support behind Gertrude Shope, who defeated Winnie Madikizela-Mandela to become the league's president.[2] At the same conference, Sisulu was elected to deputise Shope as the league's deputy president.[21] Over the next two years, she was often found at the league's downtown headquarters in Shell House.[22] However, she held the deputy presidency for only one term, ceding the office to Thandi Modise at the league's next national conference in December 1993.[23]

The mainstream ANC held its own reunion in July 1991 at the 48th National Conference in Durban, where Sisulu was elected to serve as a member of the party's National Executive Committee.[24] She only served one three-year term in the committee; at the 49th National Conference in December 1994, both she and her husband declined to stand for re-election to the party's leadership.[25]

Post-apartheid political career[edit]

In 1994, she was elected to the first democratic Parliament, in which she served until retiring four years later.[5] At the first meeting of this parliament, she had the honour of nominating Nelson Mandela as President of the Republic of South Africa.[citation needed]

In 1997, she was called before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, established to help South Africans confront and forgive their brutal history. Sisulu testified before the commission about the Mandela United Football Club, a gang linked to Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, accused of terrorizing Soweto in the 1980s. She was accused of trying to protect Madikizela-Mandela during the hearings, but her testimony was stark.

She said she believed the Mandela United Football Club burned down her house because she pulled some of her young relatives out of the gang. She also testified about hearing the shot that killed her colleague, a Soweto doctor whose murder has been linked to the group. Sisulu, a nurse at the doctor's clinic, said they had a "mother and son" relationship.

Personal and family life[edit]

Sisulu met her husband, Walter, in 1941, and their families agreed on lobola the following year; they married on 15 July 1944 in a civil ceremony in Cofimvaba.[2] Walter's best man was Nelson Mandela, and one of Albertina's bridesmaids was Mandela's first wife, Evelyn Mase; Mase was Walter's maternal cousin and had met Mandela at the Sisulus' home.[2] During reception speeches by A. B. Xuma and Anton Lembede,[2] Lembede warned Albertina that, "You are marrying a man who is already married to the nation".[27] Sisulu later recalled, "I told her it was useless buying new furniture. I was going to be in jail."[28]

The Sisulus' four-room home in Orlando West, Soweto accommodated a rotation of young relatives, including Sisulu's younger siblings and five children of their own born between August 1945 and October 1957, and Sisulu raised them alone while Walter was on Robben Island between 1964 and 1989.[2] In the early years of Walter's imprisonment, she spent her spare time sewing, knitting, and reselling eggs to raise money to cover her children's school tuition, determined that they should attend boarding school in neighbouring Swaziland rather than join the South African Bantu Education system.[2] From their young adulthood onwards, the children were also periodically detained and banned by the apartheid police between stints in exile with the ANC.[2] While Sisulu and her son were both banned in the 1980s, they received special police authorisation to be allowed to speak to each other, in exception to provisions that criminalised gatherings between banned individuals; since they lived in the same Soweto home, Sisulu dismissed the rule as "nonsense",[6] joking, ''What was I supposed to do? Not ask him what he wanted for breakfast?''[15]

Sisulu was rarely able to travel to Cape Town to visit her husband on Robben Island,[29] but Ruth First said of their marriage in 1982 that, "His capacity to lead and her political strength are... the product of a good marriage, a good political marriage, but a good marriage, one that is based on genuine equality and on shared commitment."[28] Sisulu herself famously said, "We loved each other very much. We were like two chickens. One always walking behind the other."[30] On another occasion, she reflected:

[Y]ou know, of all the people around here, he’s the only one – perhaps there are one or two – who are progressive. I was emancipated the day I got married. There was no question of 'Go and make tea' or 'Polish my shoes.' He used to wash his children and put them to bed. You know, I never felt I was a woman in the house.[31]

On 10 October 1989, Sisulu was visiting Mandela at Victor Verster Prison when she learned of her husband's impending release through an SABC broadcast.[32][33][34] His health had deteriorated in prison and when Sisulu was nominated to stand for Parliament in 1994, Mandela suggested that she might decline the nomination in order to care for Walter. Her children were so incensed by the suggestion that Mandela called to apologise to them and rescind his advice.[35] The couple lived in Orlando until after her retirement, when they moved to the Johannesburg suburb of Linden.[36] Walter died at home on 5 May 2003 in Sisulu's presence.[37] At his funeral, one of their granddaughters read a poem that she had written, titled, "Walter, what do I do without you?".[38]

The Sisulus' children also went on to hold positions of influence in post-apartheid South Africa. Their biological children were Max (born August 1945), Mlungisi (born November 1948), Zwelakhe (born December 1950, during an ANC national conference), Lindiwe (born May 1954), and Nonkululeko (born October 1957).[2] Max's wife, Elinor Sisulu, published a biography of her parents-in-law in 2002 entitled Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime.[39] The Sisulus also adopted Walter's sister's two children, Gerald and Beryl Lockman (born in December 1944 and March 1949 respectively), and raised the son of Walter's cousin, Jongumzi Sisulu (born 1958).[2] At the time of her death, Sisulu had 26 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.[4] Despite her former Catholicism, she raised her children in the Anglican Church at the wishes of Walter's mother;[2] by 1992, however, when asked whether she and Walter were still practising Christians, she replied, "There’s no time, my dear".[40]

Death and funeral[edit]

Sisulu died unexpectedly at her home in Linden on 2 June 2011, aged 92. She was watching television with some of her grandchildren when she had a coughing fit and lost consciousness; paramedics were not able to revive her.[41][30] She was buried on 11 June next to her husband's grave in Croesus Cemetery in Newclare, Johannesburg.[42]

Obituaries and tributes to Sisulu celebrated her as the mother of the nation.[3][41][43][44] In his own statement, President Jacob Zuma said that, "Mama Sisulu has, over the decades, been a pillar of strength not only for the Sisulu family but also the entire liberation movement, as she reared, counselled, nursed and educated most of the leaders and founders of the democratic South Africa".[45] He also announced that Sisulu would receive a state funeral, and that the national flag would be flown at half-mast from 4 June until the day of her burial on 11 June.[46]

Memorial services were held throughout the week,[47] followed on 11 June by the official funeral at Soweto's Orlando Stadium.[48][49] President Zuma delivered a eulogy, after leading the crowd in verses of struggle song Thina Sizwe,[50] and Graça Machel read a message from former President Mandela which heralded Sisulu as his "beloved sister" and as the "mother of all our people".[42]

Honours[edit]

The city of Reggio Emilia, Italy granted Sisulu honorary citizenship of the city in 1987,[51] and the following year, the Sisulu family was jointly awarded the Carter Center's Carter-Menil Human Rights Award, though neither Sisulu nor her husband – banned and imprisoned respectively – could travel to Georgia to accept the prize.[15] In 1993 she was elected as president of the World Peace Council.

After the end of apartheid, she was awarded honorary doctorates by the University of the Witwatersrand in 1999, the University of Cape Town in 2005, and the University of Johannesburg in 2007.[52][53] On her 85th birthday in 2003, she was present at the unveiling of the Albertina Sisulu Centre, a community centre built by the City of Johannesburg in Orlando West to serve children and adults with special needs.[54] In 2004 she was ranked 57th in SABC3's controversial Great South Africans poll,[55] and in 2007 she received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the annual Community Builder of the Year Awards, hosted by SABC, Old Mutual, and the Sowetan.[56] She also received the Order for Meritorious Service.

In 2007, the Gauteng Provincial Government announced that it would rename the R21–R24 highway system between Pretoria and the O. R. Tambo International Airport as the Albertina Sisulu Freeway.[57][58] In line with this decision, the Johannesburg Metropolitan Council resolved in 2008 to rename 18 municipal roads after Sisulu, thereby preserving the name change in the non-freeway sections of the R24 that pass through downtown Johannesburg.[59] The renaming of the R24's freeway and non-freeway sections was completed in 2013.[60][61][62] Outside of South Africa, the Albertina Sisulu Bridge, which crosses the Scheldt, was given its name by the City of Ghent, Belgium in 2014.[63]

In 2018, the centenary of Sisulu's birth, the South African government held a number of further initiatives to honour Sisulu. As part of this programme, the South African Post Office launched a commemorative stamp,[64] and a rare species of orchid, brachycorythis conica subsp. transvaalensis, was renamed the Albertina Sisulu Orchid during a ceremony at the Walter Sisulu Botanical Garden.[65] The national government hosted the Albertina Sisulu Women's Dialogue in Johannesburg,[66] and UNICEF co-hosted another Albertina Sisulu Dialogue in Durban during that year's National Women's Month,[67] In 2021, the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Innovation launched the Albertina Nontsikelelo Sisulu Science Centre, a green technology science centre in Cofimvaba, Eastern Cape.[68]

References[edit]

- ^ Bearak, Barry (5 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu, Who Helped Lead Apartheid Fight, Dies at 92". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Elinor Sisulu (2003). Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime. New Africa Books. ISBN 0-86486-639-9.

- ^ a b c d e Herbstein, Denis (12 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu: Nurse and freedom fighter revered by South Africans as the mother of the nation". The Independent. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b McGregor, Liz (6 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Bell, Jo (2021). On this day she : putting women back into history, one day at a time. Tania Hershman, Ailsa Holland. London. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-78946-271-5. OCLC 1250378425.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Lelyveld, Joseph (24 August 1981). "A Soweto Woman Regains Her Political Voice". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Fifth banning order for Albertina Sisulu". South African History Online. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Lelyveld, Joseph (17 June 1982). "South African Police and Youths Clash Outside a Church in Soweto". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Lelyveld, Joseph (2 July 1983). "Pretoria Ends Banning Orders for 50". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "S. Africa Jails Woman Weeks After Lifting 17-Year House Arrest". Washington Post. 9 August 1983. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Nontsikelelo Sisulu | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ michelle (25 May 2012). "Dr. Abu Baker Asvat".

- ^ "Sisulu and the Unity of Struggle". Washington Post. 11 May 1988. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Pen portraits of a dozen of those banned yesterday". The Mail & Guardian. 25 February 1988. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Perlez, Jane (27 June 1989). "Apartheid Foe Gets Passport And Is Expected to Meet Bush". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Seekings, Jeremy (2000). The UDF: A History of the United Democratic Front in South Africa, 1983–1991. New Africa Books. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-86486-403-1.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu addresses a major anti-apartheid rally in London". South African History Online. 15 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "South African Dissident Calls For U.S. Pressure". Washington Post. 30 June 1989. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Bush Listens to a True Voice of South Africa". Washington Post. 25 July 1989. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Walter Sisulu, in the Wake of Mandela". Washington Post. 1 October 1991. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Winnie Mandela's Defeat In ANC Vote Is Hailed". Christian Science Monitor. 30 April 1991. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Shaka Sisulu: The Gogo stories". The Mail & Guardian. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ 'For Freedom and Equality': Celebrating Women in South African History (PDF). South African History Online. 2011. p. 26.

- ^ Ramaphosa, Cyril (1994). "Report of the Secretary-General to the 49th National Conference". African National Congress. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ "1994 Conference". Nelson Mandela: The Presidential Years. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ Sisulu, Elinor (10 June 2011). "Tribute: Life, love and times of the Sisulus". The New Age. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ "Obituary: Walter Sisulu". The Mail & Guardian. 6 May 2003. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b Green, Pippa (1990). "Free at last". The Independent. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "A South Africa Choice: See Husband, or Son". The New York Times. 18 May 1987. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b Smith, David (3 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu, one of 'mothers' of liberated South Africa, dies aged 92". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu: The 'Mother' of South Africa's Freedom Fighters Fights On". Los Angeles Times. 19 July 1992. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Green, Pippa (9 June 2011). "Albertina Sisulu's Story of Persecution and Suffering, Love and Triumph". allAfrica. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Black Leaders To Be Released In South Africa". The New York Times. 11 October 1989. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Sparks, Allister (15 October 1989). "S. Africa Frees Sisulu, 5 Other Black Activists". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Sisulu, Elinor (15 December 2013). "Nelson Mandela remembered by Elinor Sisulu". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "MaSisulu: mother in jail, mother in the suburbs". City of Johannesburg. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Lelyveld, Nita (6 May 2003). "Walter Sisulu, 90; Political Leader Helped Shape Anti-Apartheid Fight". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "'What do I do without you?'". The Mail & Guardian. 18 May 2003. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Suttner, Raymond (7 February 2003). "A revolutionary love". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu: The 'Mother' of South Africa's Freedom Fighters Fights On". Los Angeles Times. 19 July 1992. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Albertina Sisulu 'was truly the mother of the nation'". The Mail & Guardian. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Madiba mourns his 'beloved sister' Albertina Sisulu". The Mail & Guardian. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu 1918–2011: Tributes". Sunday Times. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "In quotes: Albertina Sisulu remembered". BBC News. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "MaSisulu – mother to a nation". Business Day. 3 June 2011. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "SA mourns anti-apartheid icon 'Ma' Sisulu". The Namibian. NAMPA. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011.

- ^ "Sisulu's funeral to be held at Orlando Stadium". The Mail & Guardian. 5 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu funeral held in South Africa". BBC News. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu's final journey". The Mail & Guardian. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Zuma celebrates Sisulu, the 'outstanding patriot'". The Mail & Guardian. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Reggio Emilia and SA's liberation struggle". Africa Reggio Emilia Alliance. 3 September 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Liberation leaders honoured for their contributions to democracy". University of Johannesburg. 19 April 2007. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Four honorary degrees for grad". University of Cape Town. 5 December 2005. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu Centre Opened in Soweto". BuaNews. 22 October 2003. Retrieved 10 June 2024 – via allAfrica.

- ^ "The 10 Greatest South Africans of all time". Bizcommunity. 27 September 2004. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Steve Biko, Albertina Sisulu, Beyers Naude honoured as great South Africans". Sowetan. 5 December 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Gauteng to rename R21/R24 road to Albertina Sisulu Drive, 30 Aug". South African Government. 28 August 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "R21 renamed Albertina Sisulu". News24. 30 August 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Ma Sisulu's name to be on 18 Joburg streets". IOL. 10 September 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Maseng, Kabelo (21 October 2013). "Market Street makes way for Albertina Sisulu". Rosebank Killarney Gazette. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Zuma renames R24 after struggle hero". South African Government News Agency. 20 October 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Albertina Sisulu Road heralds a new era". IOL. 8 July 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Gent eert anti-apartheidsleiders met straatnamen bij de Krook". HLN (in Dutch). 24 October 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "South Africa honours Albertina Sisulu". Vuk'uzenzele. May 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Orchid to be named after Albertina Sisulu". Jacaranda FM. 6 July 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Women honour Albertina Sisulu". Sowetan. 11 November 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "UNICEF salutes the legacy of Albertina Sisulu". UNICEF South Africa. 25 August 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "Minister launches science centre". News24. 14 October 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

External links[edit]

- Albertina Nontsikelelo Sisulu at South African History Project

- Albertina Sisulu Timeline: 1918–2011 at South African History Project